HTH Says

Tuesday, 10 July 2018

Stranger On A Bench

Wednesday, 18 May 2016

Looking at field evidence from around the world, to understand where and how natural habitats actually protect coastlines

Friday, 10 October 2014

Coastal salt marshes: an effective line of defence during storms

A unique laboratory study demonstrates that coastal salt-marshes can reduce the heights of waves by nearly 20% under storm conditions.

In the largest ever experimental study for this purpose, researchers from the UK, the Netherlands and Germany demonstrated that coastal salt-marsh regions can reduce wave heights by nearly 20% over a 40 m length of vegetation under storm conditions, making these habitats an important coastal defence measure alongside seawalls and levees.

Why is this relevant?

Roughly one-fifth of the world’s population lives near a low-lying coastline. Increasingly frequent storms – like the winter storms that battered southern England - and rising sea-levels – e.g. in Miami - mean that these 1+ billion people and their properties are increasingly at risk of being flooded. At the same time adopting a single defence strategy such as building walls to protect entire stretches of coastline or relocating entire settlements away from a threatened coastline, is often impractical.

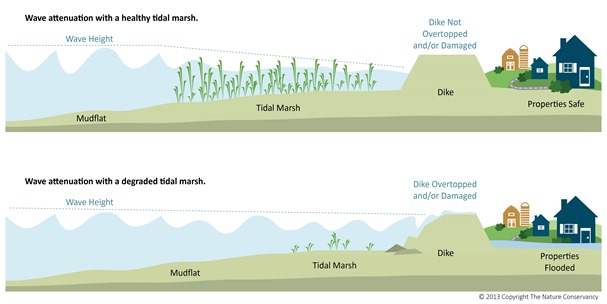

Several countries are now recognising the benefits of using coastal inter-tidal habitats (i.e. habitats that are partly submerged during high tide) to help reduce the risk of coastal flooding and erosion. Salt-marshes, mangroves and other inter-tidal habitats can protect coastlines by reducing the energy of incoming waves, like trees in a forest reduce the energy of the wind through them. As a wave travels through the vegetation, it spends energy in interacting with the plants and is thus smaller and less forceful by the time it reaches the shore, therefore causing less damage. In fact, mangroves, wetlands and salt-marshes have often received wide attention for their protective roles especially in the immediate aftermath of hurricanes, cyclones and tsunamis. Actual use of such habitats for coastal defence is however still very limited. In part, this is due to a lack of knowledge on many issues such as: their effectiveness as coastal defences ; the best ways to manage them for this purpose and ; their economic viability.

The experimental study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, answers three key questions regarding the effectiveness of salt-marshes that should go a long way in informing and encouraging their use as coastal defences.

1. How do we measure what happens in a salt-marsh during a storm?

This is, as one would expect, a fundamental question that needs answering before the discussion on whether to use marshes for storm protection even begins. However, relevant answers remain scarce. Though numerous field and laboratory measurements of wave reduction by mangroves and salt-marshes have been conducted, almost all of these are taken under relatively calm conditions of low waves and low water levels.

The main reason for this is straightforward: it is very difficult, if not impossible, to go out and measure waves, water levels and marsh properties during a storm. And, due to the complex relationship between physical marsh properties and the processes of wave and water flow through them, an experimental study needs to be both large (to minimise scale effects) and carefully constructed to replicate the natural environment as closely as possible.

This experiment achieves both of these conditions by a unique combination of measures:

- Using the largest freely accessible wave flume in the world (300 m long, 5 m wide, 7 m deep)

- Simulating realistic storm conditions of high water levels (2 m above the bed) and high waves (heights of up to 0.9 m)

- Simulating natural salt-marsh conditions by transplanting a patchwork of mixed salt-marsh blocks from a physical location on the North Sea coast

By taking these measures, the researchers ensure that their experiment comes as close as is practically possible to actual storm conditions. The next step is to measure salt-marsh performance to see if they actually help during a storm.

2. Do salt-marshes actually help during a storm?

The process of wave energy reduction within a marsh is relatively well-understood under calm conditions, but little is known about what happens during a storm.

To find out, the researchers subjected the marsh vegetation in the flume to a barrage of waves of different types, lengths and peak heights. The results are promising. They show that a 40 m length of marsh vegetation between the incoming waves and the shoreline, reduced the heights of incoming waves by up to 19.5%. In a situation resembling the simulations, this would translate to a reduction of 0.16 m (or half a foot) in the incoming wave which can result in a significantly cheaper sea defence (link to a research document) at the shoreline.

A frequently asked question is whether this reduction is due to the marsh vegetation, or due simply to the topography. A comparison between a vegetated surface and a mowed surface showed that 60% of the observed reduction was due to the marsh vegetation and 40% due to the topography. Marsh vegetation thus plays a demonstrably significant role in reducing wave heights during a storm. But the question then is, would these marshes survive during a storm?

3. Can these salt-marshes survive a storm?

As with any engineering structure we will need to know to what extent salt-marshes can survive a storm, if they are to be used as defences. The experiment therefore also measured the extent of damage to the salt-marshes from the incoming waves. After two days of being subjected to high energy waves (a typical storm lasts 1-2 days), a total destruction of 31% of the marsh vegetation was observed. Importantly, even though the vegetation was destroyed the soil substrate remained undamaged.

It is well-recognised that salt-marshes and other habitats help reduce coastal erosion by stabilising the soil. This experiment shows that this service is provided even during storm conditions. Thus, even assuming a worst-case scenario where all the surface vegetation is destroyed the substrate stabilised by the marshes would continue to reduce waves, albeit to a lesser degree.

In summary, the study assesses the behaviour of salt-marshes during a storm and shows that they can survive storm conditions to effectively reduce wave heights and also reduce erosion by stabilising the substrate. So, what?

So, what?

Many countries, such as the Netherlands, the UK and the USA are actively seeking to include natural coastal habitats within their flood defence and risk reduction measures. Salt-marshes occur widely across temperate and sub-tropical latitudes and can therefore play a significant role in such measures. These marshes are however increasingly threatened by human activity and climate change, and often find themselves squeezed between a seawall and rising sea-levels, with no room for backward or upward (i.e. to higher ground) expansion. Urgent action is therefore needed to protect them where they exist.

By demonstrating that salt-marshes can play an important role in coastal defence alongside seawalls and levees this study contributes and adds impetus to improving research, understanding and management of coastal habitats world-wide.

Thursday, 11 September 2014

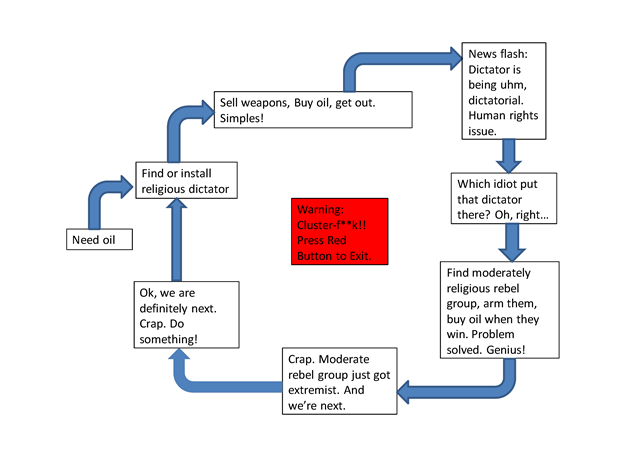

The Cluster-Fu*k Chakra

Inspired by the latest news that the US will fund Saudi Arabia to “train and arm moderate rebels to fight the ISIS.”

Sunday, 20 July 2014

White-washed Histories

Caveats: I have formed my opinions on the basis of information I could find online about school history syllabi in different countries, which wasn’t much. If I am wrong in what I say please let me know! Also, this post is a non-personal reflection on the attitude of governments and public institutions in the West and has nothing to do with my friends and colleagues in these countries most of whom are well-informed and know better than to trust history textbooks : ).

Six years ago I visited the concentration camp at Auschwitz and one lesson has stayed with me from that trip – that we should not forget past atrocities. Indeed, one of the first things that struck me when I moved to Europe was the very high degree of awareness amongst Europeans – especially Germans, of the terrible evils of Nazism and the Holocaust. At first this seems a trite and self-apparent observation. Who would not be aware of atrocities committed in or by their country in a past that is still so recent? As it turns out, the Germans are the exception in the West (Europe and the U.S.A).

Every German and almost every European and American learns of this dark period in history lessons at school. And that, without question is how it should be. But increasingly I am starting to wonder – why is it that no other western nation teaches their school-going students the history and consequences of their past misdeeds in Asia, Africa and the Americas?

Between 12 and 29 million Indians died in the Madras and Bengal Famines during English rule in India. During both famines the English government not only ignored the plight of the starving millions, they actively ensured that most of the grain and wheat grown was shipped back to England to feed more worthy causes and lives. Just enough grain was retained to feed the rulers and keep their staff alive. In fact some say that during the Bengal Famine crisis in the 1940s Winston Churchill was vocal in his contempt, hatred and disregard for Indians as they starved and what little food they had was snatched away from them. Are these facts taught in school history lessons in the UK? How many students learn of the torture of prisoners in the Cellular Jail in the Andaman and Nicobar islands and the wanton massacre of innocent, unarmed protesters at Jallianwala Bhagh in Punjab? And this is just India. The Kenyans recently won a landmark case in a UK court, with the court directing the English government to compensate the families of those killed in the Mau Mau uprising. Do this uprising, the massacres that followed, the concentration camps for the survivors or the death sentences of any suspected rebel find a mention in school history textbooks in the UK? From some preliminary research, the answer seems to be no, not unless the student specialises in history in their A-levels.

The Dutch in Indonesia were no less brutal. Victims of the Rawagade massacre in Indonesia (a much smaller number than killed in the Holocaust or the Indian famines) recently won compensation from the Dutch government for the atrocities they committed. Prior to the judgements however, the Dutch government stated that they thought the “time for persecution” had long expired. A few years ago, a Dutch journalist was taken to court for writing about some of their colonial misdeeds in Indonesia and were accused of “tarnishing the name of Dutch soldiers.” Do schools in the Netherlands teach students about their colonial history in Indonesia beyond a passing mention? Or is it left for the specialists of history to learn?

The Spanish in South America, the French in Algeria and Vietnam, the Belgians in Congo, the U.S.A more recently in Afghanistan and the Middle East – all have committed atrocities that while in absolute number maybe less than the Holocaust are just as shocking in their sheer evilness and utter disregard for human values. The debate in Germany and the rest of Europe on how best to teach pupils about the Holocaust is endless and very public. Why is it there are no similar discussions on how and why colonial atrocities should best be taught in schools? There was one debate in England on this topic – when the government decided to include the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in their Empire Studies curriculum they were accused of having an anti-British bias! The Belgians seem to be somewhat better from this perspective. Schools in Belgium have reportedly evolved from being quiet on the subject of King Leopold to being highly critical of his regime.

I agree that every country has the right to be a bit self-obsessed and self-serving when teaching history to its children. Yes, by all means highlight your achievements and your positive aspects. And yes, in today’s increasingly online world where Wikipedia and Google know everything some may say such teachings are unnecessary. But the teaching of history in today’s internationalised world – at least in my opinion, should aim to give students a balanced, if basic, view of the world and make them think about the past events that have shaped it. The wealth of the west was built – at best partly and at worst entirely – on the backs of their colonies in Asia, Africa and South America. Just as the families of the victims of Hitler’s mania deserve that their history be taught to every school student don’t the families of colonial era victims deserve a mention in the history textbooks of the countries that perpetrated these horrors?

One counter –argument is that the Holocaust is taught because it was unique as being primarily a genocide motivated by hate, unlike the colonial atrocities which were consequences of wars and suppression of internal unrest. That, in my opinion is a complete cop-out that only seeks to highlight the apparent, continuing disregard in the West for the history of their misdeeds in Asia, Africa and South America. Or is it the terrible truth that if the Holocaust had happened in a small unheard-of African country it would have been forgotten by the rest of the world?

Paradoxically, even I didn’t learn about the Bengal and Madras famines in school in India and think our history syllabi have a rather pro-British bias but that is a topic for another rant.

Tuesday, 10 June 2014

The Drawing Book

This is a story about a young girl who loved to draw. Its a hand-me-down - I was told it by my grandfather, he by his grandfather and so on. Around 310 BC, the story goes, my ancestors lived in a hot, dusty, tiny village of some 50 houses in northern India, in the present state of Rajasthan. The ancestor in question, Mohanlal Sharma – or Mollu as he was called was a short, studious, cross-eyed, 14 year old geek. Not satisfied with the misery handed to him by mother Nature and the local bullies, Mollu cemented his social position as the village clown by befriending the only person stranger than him – a girl known simply as Neelu. She was the subject of every evening conversation by the cooking fires in that village and she is, naturally, the subject of this story.

You see, Neelu didn’t have any other name. Even Mollu the village clown had a name and a family and a lineage. But no one knew where Neelu had come from, who she was or even who her parents were. The only thing the villagers knew was what her widowed father, the village chief told them – that she was adopted by him as a baby on his pilgrimage to the Jhelum river 15 years previously. And what a child he had adopted! She was fair-skinned, blue-eyed with light hair – and worst, for a young girl – tall. The village rumour was that she was in fact the daughter of a Greek soldier in Alexander’s invading army but the chief refused to encourage that belief. Despite being an obvious target however, she was never picked on. This was not out of deference to her father but out of a fear of her. For Neelu was not just different physically, she had a mysterious power. And this mysterious power would culminate – as they always do – in a mysterious incident.

10 years prior to this incident, she came home with a book she had found lying in a maize field. It was blank with a brown hide-bound cover and the paper was thick and rough but of sturdy quality. Neelu loved drawing so she grabbed a piece of chalk and in the fading light of the evening she drew a camel with two humps and a bell around its neck, looking very lost in a maize field. Next morning she was woken up by a great furore as the entire village rushed to the field to see a fantastic sight – for this part of the world only had one-humped camels and no one had ever seen the strange creature wandering about, its bell tinkling away in the early morning breeze. One wizened old villager claimed he had heard of such camels roaming the lands beyond the Himalayas, but to everyone else it was a miracle. Like any other child, Neelu was a little scared and very excited by what she knew. She rushed home to test the book and drew a rain-cloud and what do you know, that very evening it rained!

Naturally it was very, very hard for her to keep her secret and it soon became widely known that Neelu was not only strange, she was possessed by the gods (if you were her dad) or a demon (if you were a bully). Long story short, Neelu was quietly teased behind her back and begged, cajoled and harassed to her face because what more could anybody want than to have their every wish come true from the pages of a book? She very quickly learnt its rules – she could draw whatever she wanted but she could not draw the impossible into existence (she tried drawing a four-headed horse, but it didn’t work). And every time she thought of drawing something for herself a loud voice in her head told her she would lose her power if she did. So Neelu drew for everyone but herself – ripe fields of maize for the farmers, rain-clouds on hot summer evenings for the women, sweets, candies and trees to swing from for the kids, even lakes to cool off in for the village camels and dogs! But as her demand grew and the drawings kept coming to life she found herself increasingly isolated and feared. The only person who stayed by her side was Mollu – her constant friend and the only person to have never asked her to draw for him.

Years passed and by the time she was 15 Neelu’s fame had spread to neighbouring villages and made her something of a tourist attraction. Things came to a head when the 60 year old chief of a prosperous village came to her father with gifts and the offer of a marriage – between him and Neelu. His astrologer had advised him to marry again and marry young and he promised her father he would give her a place of honour in his household. This was an offer her father could not refuse. From the day he adopted her he had worried about her marriage and once word spread of her talent he had slept fitfully every night wondering where he would find a groom who’d agree to marry someone so… weird! He accordingly sat her down, explained the situation to her and told her to get ready for her marriage next month. Neelu protested vehemently. She had heard stories, told by travellers from other villages, about the great cities and kingdoms along the Jhelum, Beas and Ganges rivers and of the kings and princes that ruled there. She wanted to travel, to draw, maybe even find someone worthy to marry, preferably of her own age! Her father refused, angry at her stubbornness and locked her up in her room.

This put Neelu in a dreadful quandary. She could have drawn her way out of the room but that would be her last ever drawing and she’d be left standing outside her house looking very foolish. But Mollu was never far away from her and somehow he always knew what she wanted. He sneaked into her house when her father was away and let her out. Mollu had no intention of marrying yet and though he had it much easier as a boy, he understood Neelu’s feelings. Who would want to live the rest of their life with a horrible, ugly, 60 year old man?! They ran away from the village and hid in the maize field where she had drawn her first camel into existence. Mollu whispered to her that, for the first time in his life, he wanted her to draw something for him. She listened to what he wanted, then gave him a long hug and with tears in her eyes she started to draw as Mollu ran back to the village.

The next morning when Mollu led the worried search party to the maize field all they found was a single, teardrop-stained page torn from a book and on it the most exquisite drawing they had ever seen. Neelu had drawn the maize field as she saw it aglow in the setting sun. But at the edge of the field she had drawn a tall, handsome horse black as ebony with a grey diamond on his forehead and a silvery-black mane that shone when it caught the sunlight. And as Mollu had wished – she had drawn herself, a tiny girl on a tall horse, waving goodbye to the hot, tiny, dusty village she had lived her entire life in.

Monday, 9 June 2014

Traveller, Addict

Loneliness, the price I pay for Solitude

An absent home for the freedom to roam.

Strange bedfellows these two,

One blood red, the other sky blue.

I’m still not sure

which I prefer -

The joyful pain of your company

or the blissful silence of the interlude.

This I do know however –

When I’m around,

I am yours forever.

You’ll know I’m back,

Back for you

When you hear me fumbling at the door.

I have just one thing, then, to ask of you -

Please don’t think me untrue.