Labels

- Fact

- Fiction

- Home

- Impressions

- Photography

- Poetry

- Pointless Discussions

- Science and Engineering

- Travel

Wednesday, 18 May 2016

Looking at field evidence from around the world, to understand where and how natural habitats actually protect coastlines

Friday, 10 October 2014

Coastal salt marshes: an effective line of defence during storms

A unique laboratory study demonstrates that coastal salt-marshes can reduce the heights of waves by nearly 20% under storm conditions.

In the largest ever experimental study for this purpose, researchers from the UK, the Netherlands and Germany demonstrated that coastal salt-marsh regions can reduce wave heights by nearly 20% over a 40 m length of vegetation under storm conditions, making these habitats an important coastal defence measure alongside seawalls and levees.

Why is this relevant?

Roughly one-fifth of the world’s population lives near a low-lying coastline. Increasingly frequent storms – like the winter storms that battered southern England - and rising sea-levels – e.g. in Miami - mean that these 1+ billion people and their properties are increasingly at risk of being flooded. At the same time adopting a single defence strategy such as building walls to protect entire stretches of coastline or relocating entire settlements away from a threatened coastline, is often impractical.

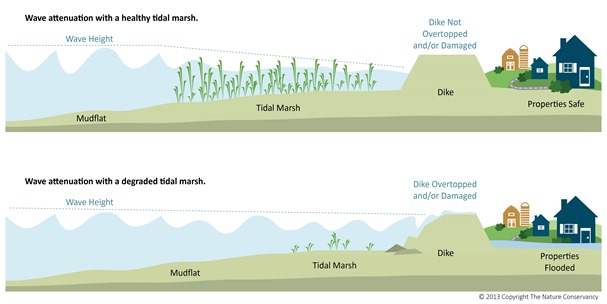

Several countries are now recognising the benefits of using coastal inter-tidal habitats (i.e. habitats that are partly submerged during high tide) to help reduce the risk of coastal flooding and erosion. Salt-marshes, mangroves and other inter-tidal habitats can protect coastlines by reducing the energy of incoming waves, like trees in a forest reduce the energy of the wind through them. As a wave travels through the vegetation, it spends energy in interacting with the plants and is thus smaller and less forceful by the time it reaches the shore, therefore causing less damage. In fact, mangroves, wetlands and salt-marshes have often received wide attention for their protective roles especially in the immediate aftermath of hurricanes, cyclones and tsunamis. Actual use of such habitats for coastal defence is however still very limited. In part, this is due to a lack of knowledge on many issues such as: their effectiveness as coastal defences ; the best ways to manage them for this purpose and ; their economic viability.

The experimental study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, answers three key questions regarding the effectiveness of salt-marshes that should go a long way in informing and encouraging their use as coastal defences.

1. How do we measure what happens in a salt-marsh during a storm?

This is, as one would expect, a fundamental question that needs answering before the discussion on whether to use marshes for storm protection even begins. However, relevant answers remain scarce. Though numerous field and laboratory measurements of wave reduction by mangroves and salt-marshes have been conducted, almost all of these are taken under relatively calm conditions of low waves and low water levels.

The main reason for this is straightforward: it is very difficult, if not impossible, to go out and measure waves, water levels and marsh properties during a storm. And, due to the complex relationship between physical marsh properties and the processes of wave and water flow through them, an experimental study needs to be both large (to minimise scale effects) and carefully constructed to replicate the natural environment as closely as possible.

This experiment achieves both of these conditions by a unique combination of measures:

- Using the largest freely accessible wave flume in the world (300 m long, 5 m wide, 7 m deep)

- Simulating realistic storm conditions of high water levels (2 m above the bed) and high waves (heights of up to 0.9 m)

- Simulating natural salt-marsh conditions by transplanting a patchwork of mixed salt-marsh blocks from a physical location on the North Sea coast

By taking these measures, the researchers ensure that their experiment comes as close as is practically possible to actual storm conditions. The next step is to measure salt-marsh performance to see if they actually help during a storm.

2. Do salt-marshes actually help during a storm?

The process of wave energy reduction within a marsh is relatively well-understood under calm conditions, but little is known about what happens during a storm.

To find out, the researchers subjected the marsh vegetation in the flume to a barrage of waves of different types, lengths and peak heights. The results are promising. They show that a 40 m length of marsh vegetation between the incoming waves and the shoreline, reduced the heights of incoming waves by up to 19.5%. In a situation resembling the simulations, this would translate to a reduction of 0.16 m (or half a foot) in the incoming wave which can result in a significantly cheaper sea defence (link to a research document) at the shoreline.

A frequently asked question is whether this reduction is due to the marsh vegetation, or due simply to the topography. A comparison between a vegetated surface and a mowed surface showed that 60% of the observed reduction was due to the marsh vegetation and 40% due to the topography. Marsh vegetation thus plays a demonstrably significant role in reducing wave heights during a storm. But the question then is, would these marshes survive during a storm?

3. Can these salt-marshes survive a storm?

As with any engineering structure we will need to know to what extent salt-marshes can survive a storm, if they are to be used as defences. The experiment therefore also measured the extent of damage to the salt-marshes from the incoming waves. After two days of being subjected to high energy waves (a typical storm lasts 1-2 days), a total destruction of 31% of the marsh vegetation was observed. Importantly, even though the vegetation was destroyed the soil substrate remained undamaged.

It is well-recognised that salt-marshes and other habitats help reduce coastal erosion by stabilising the soil. This experiment shows that this service is provided even during storm conditions. Thus, even assuming a worst-case scenario where all the surface vegetation is destroyed the substrate stabilised by the marshes would continue to reduce waves, albeit to a lesser degree.

In summary, the study assesses the behaviour of salt-marshes during a storm and shows that they can survive storm conditions to effectively reduce wave heights and also reduce erosion by stabilising the substrate. So, what?

So, what?

Many countries, such as the Netherlands, the UK and the USA are actively seeking to include natural coastal habitats within their flood defence and risk reduction measures. Salt-marshes occur widely across temperate and sub-tropical latitudes and can therefore play a significant role in such measures. These marshes are however increasingly threatened by human activity and climate change, and often find themselves squeezed between a seawall and rising sea-levels, with no room for backward or upward (i.e. to higher ground) expansion. Urgent action is therefore needed to protect them where they exist.

By demonstrating that salt-marshes can play an important role in coastal defence alongside seawalls and levees this study contributes and adds impetus to improving research, understanding and management of coastal habitats world-wide.